“There it is. Go left.”

Frank was already turning the wheel of the green Studebaker before Ida finished her instructions. They continued slowly down the curving suburban lane.

It was a bright September day, a gentle breeze whispering warm echoes of summer, as my grandparents, Frank and Ida Hanson, drove through a neighborhood just like thousands that had sprung up across the United States in the 1950s. Small, tidy ranch houses with compact lawns, new siding, and fresh paint jobs lined both sides of the road in neat configurations. In the backyards, jungle gyms, swings, and children’s toys reigned over miniature green landscapes.

Ida clutched a scrap of paper on which she had written an address in precise cursive. Behind rectangular spectacles, her eyes darted back and forth. Her hand fluttered from the camera on her lap to her hair, tucking an imaginary stray wisp back into her gray bun.

The car’s front windows were rolled all the way down, allowing the afternoon air to waft through the vehicle. Frank’s gaze held steadily to the road ahead, with an occasional glance up at their tranquil surroundings. Although the modest fringe of white hair encircling his mostly bald head signaled the departure of youth, Frank’s muscular arms, relaxed as they guided the steering wheel, remained the powerful tools of a working carpenter.

Ida leaned out the window to study the number on each house they passed.

“That’s it.” Her abrupt voice again broke their silence.

Number 117, a modest blue ranch house with a newly mowed lawn and a clump of orderly shrubs, looked much like every other dwelling in the neighborhood. The shades were drawn and the driveway was empty. Next door, a blond boy circled his tricycle around and around in the driveway, a few feet from a stocky man washing a shiny blue Ford Mainline sedan.

“Daddeeeeey, Daddeeeeey!” The child’s high-pitched, happy shriek elicited a grin from the man, whose ruddy features were reflected on the young cyclist’s round face. “Look at me, Daddeeeeey!”

“Stop before we’re in front of it,” Ida said. “Close your window. I don’t want anyone to see us.”

Whether the window was open or closed made little difference in their visibility, but after three decades of marriage, Frank knew better than to challenge Ida when her curt tone signaled agitation. He rolled up his window.

She inhaled with a quick, sharp gasp. The man next door was looking straight at the Studebaker. Did he recognize them? Probably not. After a long moment, he turned back to his gleaming vehicle, obliterating soapsuds from the fender with quick blasts of the hose.

Frank pulled over to the curb, halfway between the neighbor’s house and number 117. Across the street, a young woman in a yellow blouse, pedal pushers, and a headdress of pink curlers wielded an oversized pair of clippers as she pruned the bushes lining her front walk. Frank and Ida sat in the Studebaker, the windows rolled up, looking at the small blue house. Sweat trickled down their backs as the heat inside the car intensified.

Ida picked up the camera and pointed it at number 117. The click of the shutter echoed within the quiet, motionless vehicle. Within Ida’s mind, it felt like the slam of a hollow door.

“Let’s go and come back down the street from the other side.”

Frank pulled the Studebaker away from the curb, and slowly they wound down the road. After a hundred yards, he made a U-turn and guided the car back up the lane until they were almost in front of number 117 again, this time on the other side of the street. He halted, leaving the motor running. The woman in curlers had progressed to the side of her house, where she continued to steadily snip offending branches. Straightening up, she stared at the car again, clippers dangling from her right hand.

“You take it now,” Ida said, handing Frank the camera.

Through his closed window, Frank pointed the camera across the street at number 117 and snapped.

“Oh no, she’s watching us. We need to move. Drive down so she can’t see us.”

Nodding, Frank pulled forward a few yards until the woman was out of sight behind the corner of her house. He stopped in front of a newly planted seedling with a spindly trunk and thin, delicate branches. Twisting around in her seat, Ida stared back at the blue ranch house for a long minute, her jaw clenched. One hand still clutched the now-forgotten scrap of paper with the address.

“I wish she hadn’t seen us.” Ida’s voice broke between shallow breaths.

“It’ll be OK, sweetie,” Frank whispered, stroking her hair. “It’s all right.”

He placed the camera in Ida’s purse and wrapped his arms around her. Tears streamed down her face, and she began rocking back and forth, her shoulders heaving, the scrap of paper fluttering to the car floor.

Outside the vehicle, Ida’s moans dissipated in the swelling afternoon breeze. The seedling tree’s slender limbs quivered as the wind gained force, their bobbing shadows writhing in an unearthly waltz on the sidewalk.

Ida’s cries gradually subsided. She sat up straight and very still. Finally, she began wiping her wet eyes and cheeks with Frank’s handkerchief, while he gently caressed her shoulder.

“OK, let’s go,” Ida murmured finally in a dull, low tone.

Inside her camera, the rays of light that had beamed through the open shutter during those fractions of a second had done their work, searing hazy images into the undeveloped film. The telltale prints, unseen for the next fifty years, mutely attested to Ida and Frank’s path that September day.

“Come on, Dad,” I said. “Let me just look in the box. The pictures might have clues.”

“No.”

“Why not?” I asked.

“I don’t want to get it out. It’s depressing.”

My father, Harley, couldn’t face the box containing his parents’ photo collection, even though its contents might help solve our baffling family mystery. For decades, a rotating cast of family members had tried, and failed, to trace the family trees of his Brooklyn-born parents, Frank Elmer Hanson and Ida Agnes (Howe) Hanson. Now, a previously unknown trove of photos had the potential to breathe new life into the family project, as my dad had dubbed our investigation into his parents’ identities.

If only I could get my hands on those pictures. How frustrating it was that my dad refused to let me look at them, especially since he was the one who, years earlier, had gotten me involved in the family project. Despite his belief in seeking truth and confronting facts, my father, a retired scientist and behavioral psychologist, shrank from this one particular box of evidence.

Until he was sixty-nine, my dad was one of the four Hanson boys, brothers who had grown up during the 1930s and 1940s in a bungalow in North Hill, a working-class neighborhood of Akron, Ohio. Then, in March of 2000, my dad’s favorite older brother, Al, died abruptly of cardiac arrest. A month later, his twin brother, Harvey, was diagnosed with liver cancer. By June of 2000 Uncle Harvey was gone too, slowly inhaling one last gulp of air thirty minutes after I arrived at his bedside in a hospice in Dayton, Ohio. My father had paid his final visit a day earlier.

A month after this double blow, a box containing Ida and Frank’s photo collection arrived at the doorstep of the ranch house my dad shared with my stepmother, Carol, in an outer-ring suburb north of Philadelphia. Uncle Al’s widow, Aunt Betty, had cleaned house, shipping off Hanson memorabilia that had been consigned to the oblivion of storage ever since Frank, my grampa, died in 1982.

As soon as my dad mentioned the box, I began badgering him to let me see its contents. These photos were our last, best chance for a break in the case of our seemingly unsolvable family mystery—genetic ancestry testing being, at the time, in its untried infancy. Yet no matter whether I cajoled my dad on the phone or appealed in person when I came down from Boston, we always ended up at the same impasse.

“Can you get out the box tonight?” I’d say. “You don’t have to look at the pictures. I’ll go through them for you. I’ll just look to see if there’s anything that could help us in the research.”

“No, I don’t want to,” he invariably replied. “Maybe next time you come.”

His jaw, the strong angles of his youth now gently camouflaged by a layer of flesh, jutted forward. The subject was closed.

It seemed unfathomable that my father could refuse me access to this newly unearthed box of photos. At his request, I had begun my labors in the Hanson and Howe genealogical wilderness during college two decades earlier. For years, he had even insisted on paying me by the hour.

Although I didn’t understand why the search for his parents’ missing past meant so much to my father, I immediately loved the process of family history investigation.

“I’m more than happy to do the research, but why don’t you do it too?” I asked a few times. His reply, “I don’t have the required skill set,” made no sense, coming from a man whose trade was designing and performing research studies. However, given how much I relished being my dad’s detective, I dropped it.

Forever my favorite person in the world to talk to, my dad was willing to entertain almost any topic, with the possible exception of sports, which he regarded with profound indifference. When I was off on my own at boarding school after my parents’ divorce, in my midteens, and later at college, he was the one I called, collect from a pay phone, when I was lonely or needed advice.

“Hi, Annieeee!” he’d say after the operator put me through. Just hearing his singsong greeting, his calm voice still echoing the cadence of his hometown of Akron, Ohio, my pulse would slow down, and I’d relax. Wherever I was, whatever jam I had gotten myself into, my father’s nonjudgmental insights and comments invariably comforted me and helped me find a way forward.

My dad didn’t believe emotions mattered, professionally speaking, yet he would have made an excellent therapist and indeed had counseled many friends over the years. At Merck & Co., Inc., the drug company where he had directed laboratory research using the principles of behavioral psychology, the human resources manager had frequently sent troubled employees to him for guidance.

When it came to his own feelings and painful subjects, however, my father was stubbornly recalcitrant. “He analyzes everyone but himself,” my stepmom, Carol, remarked once before clapping her hand over her mouth, as if she had revealed too much. Nowhere was this observation truer than regarding the box of photos. The ghosts of his brothers and parents, lying silently within that container, evoked feelings that my outwardly cool and collected dad just couldn’t confront.

![]()

The Hanson family odyssey had begun simply enough in 1953, when Uncle Harvey’s new bride, Virginia, asked her in-laws if they would answer a few questions about their family trees. While in most families this would be an ordinary request, among the Hansons, it was an unprecedented strike within forbidden territory.

“They’re all dead. They died.” That was Frank’s terse response whenever my dad asked about his family back in Brooklyn.

“Everyone else I knew, the kids I played with, they all had relatives, uncles, cousins,” my dad told me. “I never had any.”

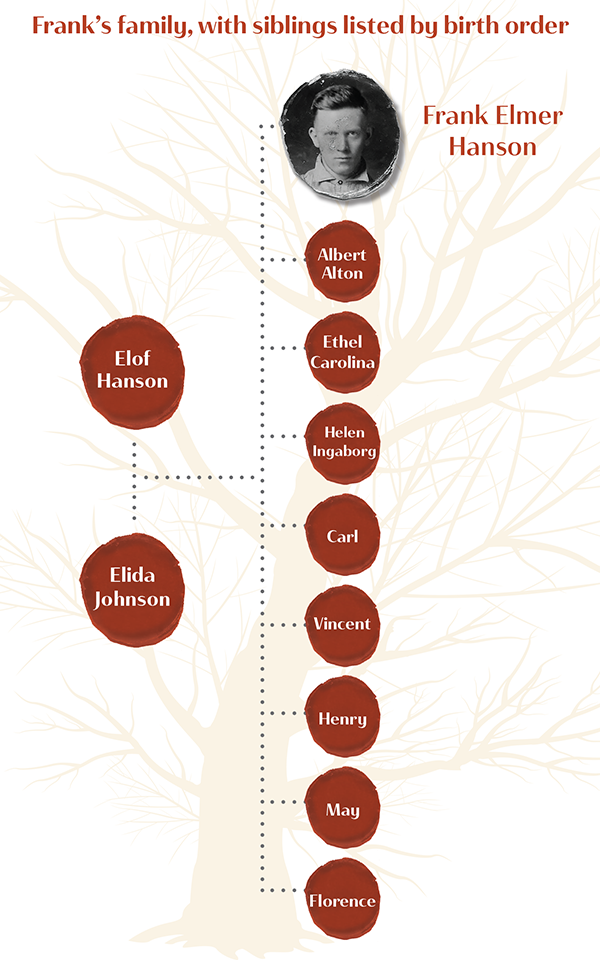

My dad’s scant knowledge of his father’s Swedish immigrant family focused on two little sisters, Florence and May, whom Frank had adored.

“My father always talked about how cute Baby Florence was, how she was his favorite,” my dad said.

The other small sister, May, died around the time of the 1918 flu pandemic, which had upset Frank terribly. He also mentioned one other sibling, Al, a musician in the US Navy.

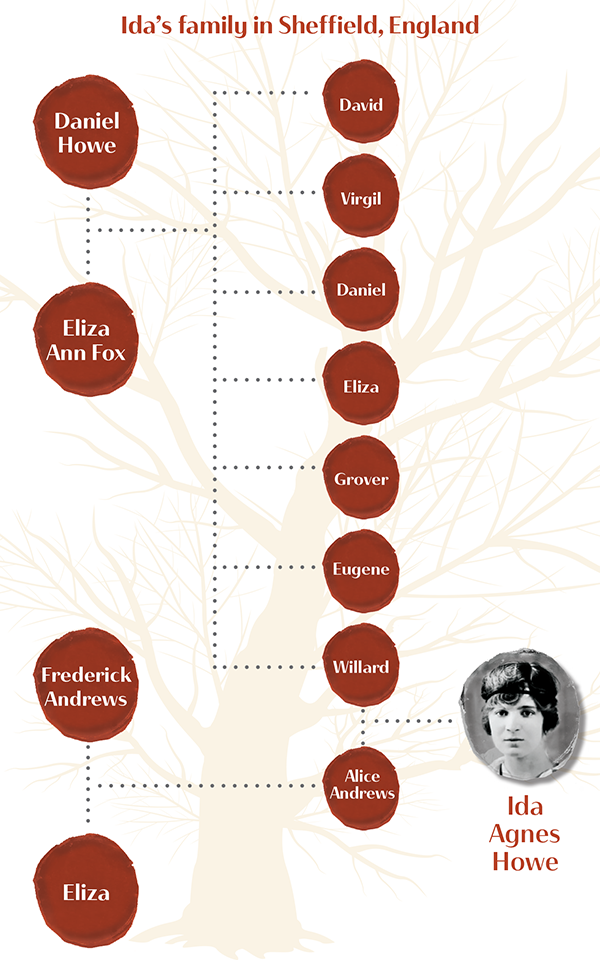

Ida always told her sons that she was the only child of a wealthy English couple who had died when she was a young girl. Her father, practically of noble descent back in Sheffield, England, had emigrated to the United States as a young man. After a brief stay in Connecticut, he’d bought a farm in Brooklyn, New York, where he’d lived the life of an English country squire. The city had taken over the land when it created Prospect Park. So substantial was her late papa’s “English fortune,” according to Ida, that she and Frank could just go to New York to get money that was coming in from England.

When new daughter-in-law Virginia asked Frank and Ida for information about their families, they acquiesced readily, despite their previous refusals to discuss their pasts. In an exchange unprecedented within the Hanson family, they divulged specific details, such as their parents’ and grandparents’ names, the names and birth order of Frank’s eight younger siblings, and even the names of Ida’s aunts and uncles back in Sheffield. Frank’s parents had emigrated from Skåne, in southern Sweden, he said. Ida also revealed the date and place of her and Frank’s wedding: They were married in New York City by a justice of the peace on May 23, 1923.

Armed with this data, Virginia, a diligent and knowledgeable librarian, spent the next three decades attempting to trace Ida’s and Frank’s family histories. Her research was a complete and utter failure. Virginia could never corroborate a single element of their stories. Nor could she identify even one ancestor who potentially belonged to us.

During Frank’s later years, if questioned about his family back in New York, his standard reply was, “I don’t remember.” Or he’d say something to the effect of, “The past isn’t important. You go on and have your own life.” Then he’d change the subject. We couldn’t ask Ida because she had died in 1960 after a battle with breast cancer.

When my sisters, Uncle Al, and I joined the family investigation in the late 1970s, our endeavors were just as fruitless as Virginia’s. Referring to her painstakingly created ancestry charts, with names and dates neatly penciled in, we devoted untold hours to both long-distance and on-site research. We visited dusty archives in locations ranging from New York City and Washington, D.C., to Columbus, Ohio, and Salt Lake City, Utah. We stared at microfilm, scrutinized birth, death, and marriage records, pored over city directories, and examined church registers and land records. While vacationing with her husband in England in the 1980s, my oldest sister, Karen, even scheduled a research detour up north to the city of Sheffield, a former steel industrial powerhouse that drew few tourists. When internet genealogy sites began developing in the late 1990s, I mined every available online source, again to no avail.

Over the decades, this family project of ours mutated into an endless spiral of doomed excursions within a murky, slippery labyrinth. Despite all our digging, the Hanson and Howe investigators failed to unearth even the tiniest speck of evidence that the families of Frank Hanson and Ida Howe had ever existed.

How could a bunch of smart people look so hard and never find a thing? If our genealogical research were a Nancy Drew mystery, its title would be “The Case of the Missing Ancestors.”

In August of 2002, I was again visiting my father and stepmother, Carol. As we drove home from dinner, I decided to ask for the pictures yet again. My father was relaxed after enjoying an extra-rare steak along with a few drinks and good conversation. This was the best chance I was going to get.

“Hey, Dad,” I said. “Let’s get the pictures out tonight.”

“No.” From the rear seat of the dark car, I could see only the back of his head, but I could envision him pursing his lips as he stared straight ahead.

“You said I could look at them next time I came.”

“You did, Harley,” Carol chimed in. “You promised. You said you’d let her see them this visit.”

“I changed my mind,” he said flatly. After a long silence, we exchanged only a handful of words the rest of the way home.

When we got back to the house, he disappeared into his private study, dubbed the “junk room,” and closed the door. Something was up. Typically, my dad’s first order of business after getting home was to change from his going-out clothes into his comfortable at-home uniform of old slacks and a threadbare but clean short-sleeved button-down shirt.

A few minutes later, he returned, staring straight ahead, clasping a battered brown cardboard box the size of a large hatbox. Avoiding eye contact, with a soft thump he placed the box in front of me on the table of the keeping room, as he and Carol called the all-purpose living area just off their kitchen.

“Don’t look at them now. I don’t want to talk about it.”

Startled, I stared at this long-sought prize, encased in its shell of brown cardboard and packing tape. I longed to tear it open and dive in, but I would have to hold out a little longer.

“OK, that’s fine,” I said, composing my face into the most neutral expression I could muster. Wordlessly, I bore my treasure down the beige-carpeted hallway to Carol’s small study, which doubled as the guest room.

Carol’s brown eyes were sparkling when I returned to the keeping room. “I think the answer is going to be in those pictures,” she said.

My father and I spent the rest of the evening chatting in the basement den as we half-watched TV, idly flicking between his favorite stations, the History Channel and public TV.

On the floor by the couch were the slippers my father always wore indoors. Until my parents split up when I was fourteen, a similar pair of worn brown leather slippers by the back door promised his return home from long hours at the Merck labs. When I was a toddler, the child of another scientist in his lab had contracted amoebic dysentery from monkey excrement the fellow had unwittingly tracked home on his shoes. Horrified, thereafter my dad had always donned slippers immediately upon entering the house, a practice he had continued after retirement. He never replaced a pair until the leather was cracking and soles splitting. Also typical of my dad was that he didn’t tell me and sisters why he always wore slippers inside. As was his way, he quietly protected us against dangers large and small.

At midnight, leaving my father downstairs still watching TV, I padded down the dimly lit hallway to Carol’s study, where the photos awaited me. Finally, after two long years, I was about to enter the hidden world housed in that simple cardboard box.

© Copyright 2025. Anne Hanson Author & New England Books, LLC. All Rights Reserved.